Evolution of Caving and Cave Diving Equipment

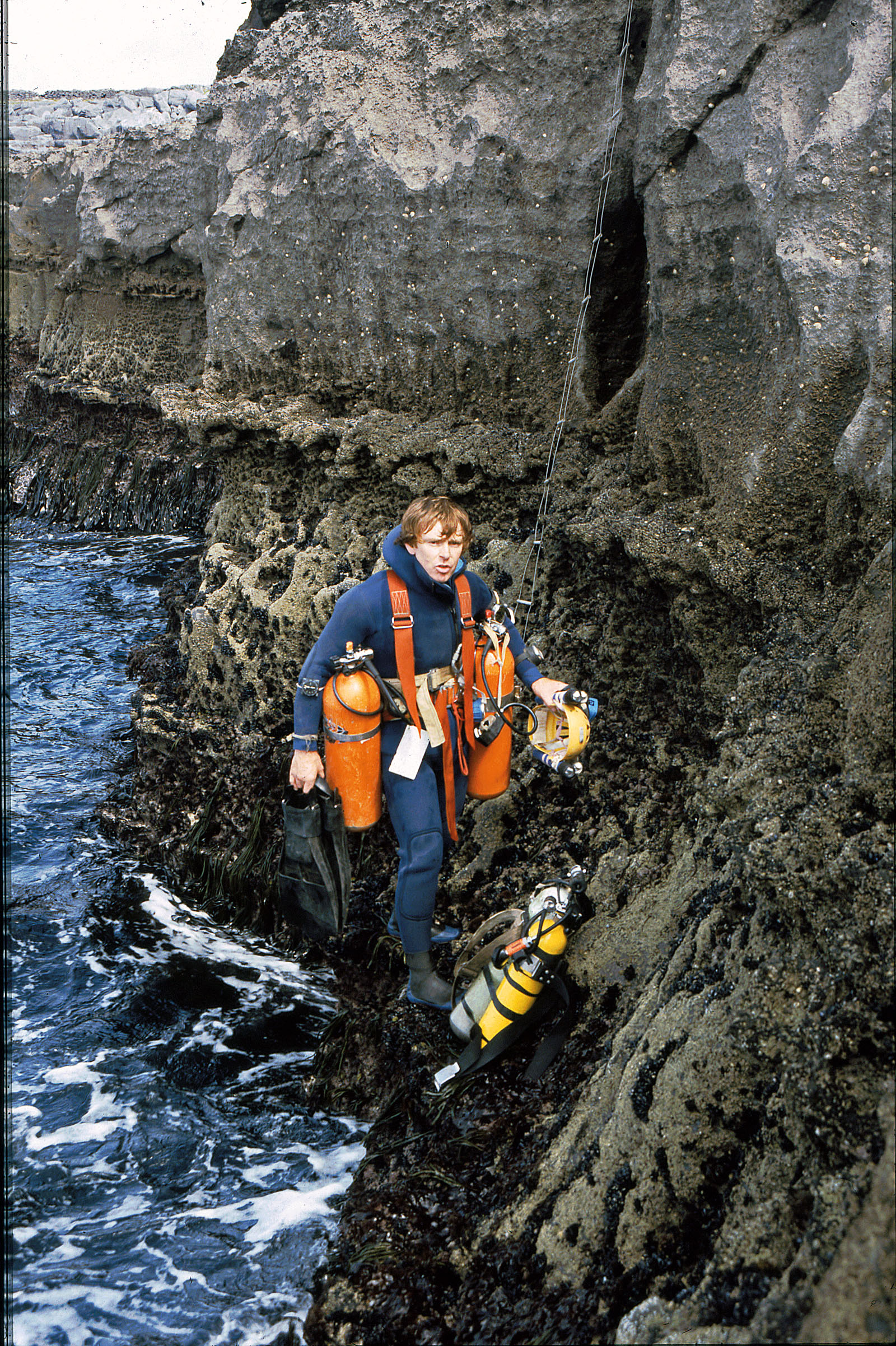

Wednesday, August 09, 2017 Caving and Climbing by adminCave diver Martyn Farr, the author of The Darkness Beckons, talks about the evolution of caving and cave diving equipment since the 1960s.

Gear has changed and evolved a lot over the fifty-plus years I’ve been caving and cave diving, and it’s obviously very difficult to cover such a big topic in a single blog post, but I thought I’d give a brief overview of some of the more significant changes that immediately spring to mind.

Back when I started caving as a boy in South Wales back in the 1960s, standard caving wear consisted of a cotton boiler suit (which as you can imagine was wholly inappropriate for wet conditions as cotton holds water and possesses next to no thermal protection) and a cardboard miners’ helmet (which again afforded little real protection once it became wet and pliable). Lighting units such as the carbide lamp or even the NiFe cell electric light were distinctly dim by today’s standards.

When I began cave diving a few years later in the early 1970s the gear was so basic – scabby old wetsuits with holes in (at least that’s what mine looked like!) and very basic lighting where the headpiece would flood but hopefully keep on working underwater (which amazingly they generally did).

Diving cylinders back in the 1970s were relatively low pressure, and few were rated for pressures in excess of 200 bar. Hardly anyone will remember that adjustable buoyancy (inflation devices), for example, arrived in the late 1970s. A lot of the problems with dive equipment in this era boiled down to poor manufacturing. On one occasion in Dan yr Ogof (South Wales), my sixth-ever cave dive, my regulator packed up completely mid-dive. I had to free-dive out; it was absolutely terrifying and it was a miracle that I survived. The problem seemed to be due to a bit of metal in the second stage of regulator left over from the manufacturing process. (I noted later, somewhat ironically, that the valve had come with a ‘lifetime guarantee’.)

Photo: Mike Coburn.

I was down there that day with two guys and neither of them went cave diving again! In fact, one of them gave me all his equipment and the very next weekend I spent a day practising swapping between mouthpieces to try and ensure this kind of thing never happened again.

Cave diving kit started improving in the mid-1970s with people like Geoff Yeadon and Oliver Statham, who introduced the first drysuits up in the Yorkshire Dales. I copied their approach at Wookey Hole in 1976/1977; I was always about a year behind those guys then in terms of gear.

In the late 1970s, regulator design was also improving and Poseidon regulators arrived on the scene. These became the workhorse of the cave diving community for many years. Over in Florida, the dual-valve manifold appeared in the 1970s, but this was of no use in Britain as the two-tank combination was wholly impractical for British cave diving. It did find application in Europe though, and became very common – in fact, there’s a memorable photo of Olivier Isler about to dive in the Fontaine de St George with a ‘jumbo backpack’ – five tanks joined together! It’s ridiculous by today’s standards, but these guys were seriously pushing the boundaries of what was possible.

Around the same time, German cave diver and all-round equipment innovator Jochen Hasenmayer started using Aquaflashes. These were heavy duty but were waterproof and a huge improvement over our previous caving headlights. Hasenmayer was arguably generations ahead of his time and was – to my knowledge – the first to use scooters (DPVs) in Europe – at sites such as the Emergence du Ressel in 1981. Again he was the first to use a rebreather in the same year. No one used such equipment in Britain till long after that, but there’s no doubt that the nature of British caves and sumps contributed to that fact.

The biggest change I can remember from the early 1980s resulted from the tragic death of Ian Plant in Bull Pot of the Witches in Cumbria in 1980. An experienced and highly respected cave diver, Ian lost the line in poor visibility and ran out of air. Geoff Yeadon consequently spent some considerable time looking at how and where lines were laid, new reels attached and all-round ‘line work’ in caves. As a result, safety guidelines were massively improved in the 1980s. To give a personal example about lines and bad practice, I was diving Far Sump in Peak Cavern in 1981. It’s about 385 metres long – at the time the longest sump in Derbyshire – and I don’t think I put down a single belay along the entire length! The line was cutting every corner and disappeared into nearly all the mud banks along the route; divers today would have been horrified! I could argue that I knew where I was going on the return dive, but the acceptance of the need for regular anchor points and belays has clearly made things a whole lot safer underwater.

In the mid-1980s, divers started experimenting with Nitrox, which has a higher proportion of O2 in the gas mix … and was nicknamed ‘devil gas’ by the regular diving community – because they said that if you used it you were going to die! But cave divers started using Nitrox and today in Florida it is a commonly used mix, significantly reducing the decompression penalty for dives in the 20–30-metre range.

In 1985, Rob Parker, during his explorations at Wookey Hole, started experimenting with helium mixtures – Trimix. This took deep diving into a whole new realm in the 1990s. Today, Trimix has diminished massively in the open-circuit sphere as it’s simply too expensive given the rising price of helium, but it’s commonly used by rebreather divers, given the relatively small amount of diluent required on deep diving projects.

Fast forward over a decade and I’d say the rebreather revolution started in the late 1990s – and continued at an increasing pace through the 2000s. Rick Stanton developed his own side-mount rebreather in 2004 for places like Wookey Hole, although there had been similar approaches on the continent where for example the Joki had appeared around this time – which the likes of Xavier Meniscus and others still use today. There are so many rebreather designs out there today, and all of them won’t stand the test of time. I personally want to be able to go into a shop and buy one knowing it works and that it comes with a solid after-sales service.

Over the last five years the most significant development, in my experience, is the evolution of battery technology. Lithium-powered batteries mean lights, scooters, cameras and video gear are vastly improved, reliable and keep going for so much longer. Water and lithium batteries aren’t a good mix, in the event of leakage, but my experience has only been positive.

In terms of the next five years, I think thermal protection will see improvements. Heating of thermal undergarments will surely increase in popularity as manufacturers continually upgrade their products and they become more affordable and accessible. This kind of gear is vital for the guys pushing the limits in caves like Pozo Azul. A lot has changed since the 1960s, and there’s no doubt it’s made the sport safer and more comfortable.